andy harper

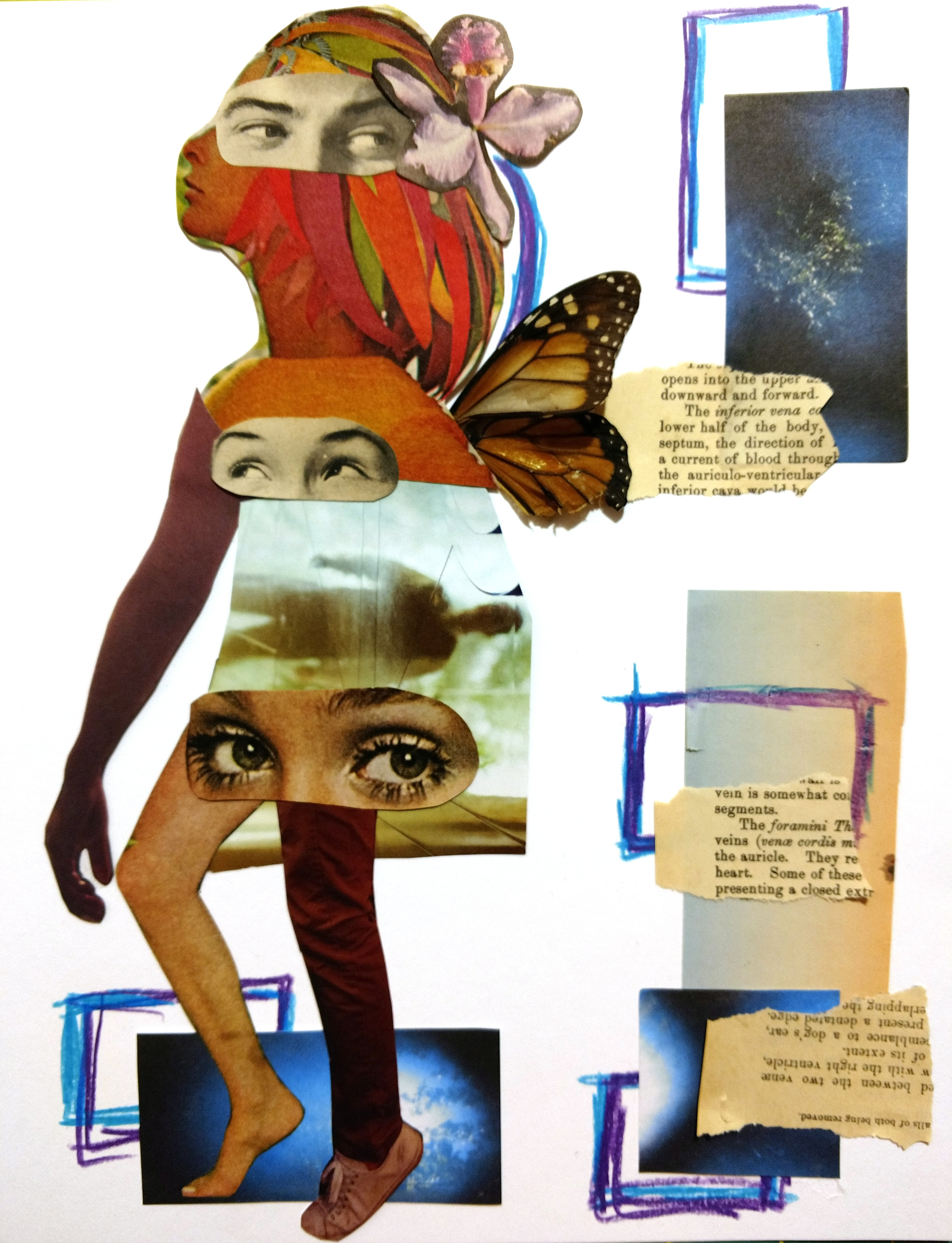

Memoirs Of A Fairy Princess

This is how it feels to be Sally: a prickling at my forehead from the tough, translucent threads that poke out stubbornly from the flap of my sofa arm protector wig. Scratchy burlap lays rigidly across the top of my forehead, half covering my ears. It falls to the tops of my scrawny shoulder blades, where its brown, floral microfiber is folded over and more stiff thread sticks out like loose fishing line. What I want to say is, it itches. A lot. But it looks like real hair and, when I look in the mirror, I am like a real girl. I am four, maybe five years old. At daycare they call me something else. But what kind of name is Andy for a fairy princess?

Among the washcloths stacked dutifully upon the corner of a shelf in our linen closet, there is a soft brown one which features in one corner a flower with white, plush petals—part of a matching set of which the bath and hand towels have been either discarded or never purchased. When I am old enough to bathe myself, I choose this one for my showers. After turning off the water, I sweep my brown hair away from my forehead and carefully drape the wet washrag over my head so that the corners fall over my temples and the large white flower sits just over one ear. I pull back the shower door to greet my transformed reflection.

The washcloth wig isn’t as long as the arm cover wig, but it is still too much hair for a boy, and the flower really does the trick. After my shower, I supplement the look by wrapping a bath towel around my chest, like my mom does. I spin for the mirror, for a score of imaginary photographers, then sit down on the toilet lid, crossing my legs the ladylike way. A second towel becomes a shawl or a layered dress. Stepping onto the toilet lid, I view my perfect, slender body in the wide mirror over the vanity, admiring the lay of the damp towel over my hips and butt. When I sit down, I bend at the waist to peek up my own skirt.

I have been called effeminate – most recently by a woman I dated briefly in Omaha, who also said that my best attribute was my penchant for exaggeration. She could be a pretty mean drunk and, in the end, I don’t suppose she ever got to know me especially well, but that accusation hit home. My closest friends have refuted her claim, and what they’ve said sounds right to me. Nonetheless, I don’t feel quite comfortable calling myself “masculine,” and maybe that’s just because I don’t want to invite argument.

“Well, you can hardly think of yourself as masculine,” slurs the woman from Omaha. “When was the last time you wrangled cattle?”

Growing up, whenever I had to refer to myself in a gender-specific way, I squirmed and used the word “guy.” “Boy” didn’t do justice to my advancing adulthood, but “man” didn’t feel quite right either. Again, I think I didn’t want to invite argument; if I referred to myself as a man, someone might give me a detailed list proving I wasn’t one. In my small, rural Missouri hometown, manhood was farming and football; I was piano and marching band. Justin McFadden, the childhood friend who told me I couldn’t be a farmer because I dressed “too preppy” made more or less the same argument against my masculinity. I wasn’t rough enough, wasn’t tough enough, didn’t know anything about cars—but, then, what nine-year-old did? Later, in my freshman year of high school, I became a woman to the boys at the back of my school bus when I didn’t join the football team. Because I was afraid of heights and driving fast, I had no balls, became a pussy. As so many guys from my school graduated and joined the military—a prospect I rejected both as a pacifist and as someone who didn’t like the idea of becoming government property—I began to wonder what options lay open to me beyond wrangling cattle and soldiering up.

Noel Perrin begins his essay, “The Androgynous Man,” by setting a scene: “The summer I was 16, I took a train from New York to Steamboat Springs, Colo., where I was going to be an assistant horse wrangler at a camp.” (One point to the woman from Omaha.) He goes on to recount an inkblot personality quiz he took titled “How Masculine/Feminine Are You?” in a magazine—and his unsettlingly feminine score. On critical inspection of the “masculine” answers, he observes that the makers of the quiz have identified manliness with machinery and violence, while art and natural objects make up the purportedly feminine responses. He concludes that there’s more to maleness and femaleness than the test makers have taken into account—and that there’s more room for play between the two.

“What it does mean to be spiritually androgynous is a kind of freedom,” he writes. While traditionally masculine men may feel perfectly at home in their more conventional forms of gender expression—and, indeed, may truly enjoy taking in a football game now and then—their more androgynous counterparts have a wider range of options available. Unfortunately, many men are “too busy trying to copy the he-man ever to realize that men, like women, come in a wide variety of acceptable types.” According to Perrin, men who eschew the self-conscious imitation are free to indulge in the pleasure of nurturing children, kissing cats, and showing emotion. I was a senior in high school when I encountered Perrin’s essay, and because I had already made an appointment with a Marine recruiter by the time I read it, his revelations meant two kinds of freedom. I had permission to be just the kind of man I already was.

When I am eleven years old, my cousin Jonie comes to spend the summer with us. We swim when it’s warm enough, take picnics to Honey Creek, build blanket forts in the living room. We have a favorite game, which we call “Bookshop.” It involves tearing all the books from all the shelves in our house—the particle-board-and-veneer towers of Goosebumps and My Babysitter is a Vampire/Has Fangs/Bites Again and the dusty glass-front shelf at the end of the hall filled with my parents’ Louis L’Amour and Barbara Delinsky—and relegating them to my brother’s bedroom where they stand in rows in dresser drawers and on desktops and lay neatly open on every other surface. Matt and Jonie play the store owners and it is up to me to portray a colorful array of customers. There are Billy Bob and Jim Bob—each an amalgamation of overalls and hick accents—and a stuffy British gentleman, an encroaching corporate figure, ever concerned with the management of the store. Matt and Jonie laugh as I surprise them with each new character.

I shuffle through the door on my knees, draped in layers of flowing robes—twin-sized bedsheets and throw blankets—alternately warbling weighty prophecies of astrological demise and appealing to the spirits that haunt this bookstore. I am the “Spiritual Lady,” here to warn the unsuspecting shopkeepers of the evil spirits that have taken up residence in their establishment—until they throw me out, denouncing me as a lunatic. Enter next the “bombshell,” all flowing arm cover wig and two plush footballs from the Big Dog store squeezed between the top of my bath towel mini dress and my flat, hairless chest. I push my bust forward and squeeze my shoulder blades together, holding my arms carefully in T-rex position to keep everything in place.

My favorite character to play is that of Sandra McNulty, a strong-willed and curiously masculine female newscaster—a holdover from a fictional news broadcast I acted out in grade school. When she visits the bookshop, I complement her low, raspy voice and Brooklyn accent with a pair of red high heels and my mother’s shoulder-padded blazer. A wad of shower poufs carefully pinned to my head might sufficiently materialize the cloud of curly brown hair I have always imagined for her, but in the absence of appropriate tools I impatiently appeal to my playmates to use their imagination: “Okay, imagine, like—see, she has—” I stammer, groping at the air over my head, teasing an imaginary perm ceaselessly higher in proper nineties fashion. “Can you—do you know what I mean?”

“Female impersonators are highly specialized performers,” writes Esther Newton in Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America (1972). “In order to create the female character, female impersonators always use some props which help create the partial or complete visual appearance of a woman.” My primary props included dresses fashioned from bath towels, bedsheets, and black garbage bags; those wigs improvised from towels and washcloths, arm protectors, boxers, old t-shirts, and new mop-heads; and a variety of prosthetic breasts, including teacups, cereal bowls, tennis balls, footballs, baseball caps, wadded up t-shirts, stuffed animals, and plastic Easter eggs. Not to mention my mother’s high heels, my cousin’s bows and costume jewelry, and, occasionally, nail polish. According to Newton, “this form of specialization is thought by everyone, including its practitioners (the impersonators), to be extreme, bizarre, and morally questionable.”

But nothing about “Bookshop” or the other games involving what I’ve come to refer to as “trash bag drag” felt particularly bizarre or morally questionable. Maybe my experience doesn’t quite apply to Newton’s research after all; I was neither a career queen nor a street fairy, but an eleven-year-old kid who didn’t fit in with other boys and occasionally wondered how it would feel to be a girl. Newton posits drag as the “socialization” of the proto-female impersonator’s “underlying psychological conflict in sex role identification.” In other words, for Newton at least, from pre-memory through pre-adolescence, I was acting out the drama of my own inner crisis of gender identity. Her allegation is tough to dispute, given the uneasiness I felt in high school—and the immense relief I found in Noel Perrin’s interpretation of androgynous masculinity.

Still, there was a decidedly fictional element to my drag performances. These personae were characters whose stories evolved over the course of that summer—imaginative creations crafted with varying degrees of nuance and attention to cultural tropes. Brought before the audience of my brother and my cousin, they became theatrical roles—I might only have been an aspiring playwright. But that didn’t account for those long moments in front of the mirror, draped in damp towels and the brown, flowered washcloth. In those moments, no one was looking but me.

And yet, in the dynamic between these contextual opposites—the costume-over-clothing performance and my nakedness in those private moments—might there have resided some early wisdom? “Drag means, first of all, role playing,” writes Newton. “By focusing on the outward appearance of role, drag implies that sex role, and, by extension, role in general is somewhat superficial, which can be manipulated, put on and off again at will.” Or, as Judith Butler puts it in Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990), “In imitating gender, drag implicitly reveals the imitative structure of gender itself.”

Indeed, my male roles relied just as much on social scripts as my female roles. I think of the props I used for the male patrons of our bookshop: a globe under the shirt for a large gut, an ATV helmet, an array of neckties, a pair of Groucho Marx glasses complete with bulbous nose and bristly mustache. I knew how to perform masculinity in the same ways that I knew how to perform femininity—not by the expression of certain inherent and biologically determined qualities, but by what Butler identifies as a “stylized repetition of acts.” Furthermore, Butler asserts, “the very notions of an essential sex and a true or abiding masculinity or femininity are also constituted as part of the strategy that conceals gender’s performative character,” as well as the wide variety of expressive possibilities touted by Perrin.

“Signification,” according to Butler, “is not a founding act, but rather a regulated process of repetition.” In other words, the gender roles that many of us compulsorily perform have no empirical or biological origin or cause, but only a cultural history of enforced performativity. “In a sense, all signification takes place within the orbit of the compulsion to repeat; ‘agency,’ then, is to be located within the possibility of a variation on that repetition.” This understanding of agency resonates with Perrin’s meaning of freedom. For him, macho men were free to be their manly selves while those more androgynous ones could find agency only in their resistance of the pressure to perform. In that freedom: confidence, wholeness. Happiness.

It is the summer of “Bookshop,” and, as every summer, we are camping in the Ozarks with my father’s cousin and his family. We define “camping” as a trailer with electricity and running water in a park overlooking the Osage River, where we kids hunt river rocks in the morning before the dam opens and the water rises twelve feet on the limestone banks while my parents sip Miller Lite from nylon lawn chairs over Astroturf. In the evening, Cousin Danny and his wife Carol sit around the fire with my parents, smoking their cigarettes in halos of mosquito repellant, while towels and swimsuits hang on clotheslines strung from the trees above them. Inside the camper, Matt and I play games and watch movies with Danielle, who’s my age.

At my brother’s urging, I cobble together a costume. There isn’t much to work with around the camper. I remove my red t-shirt and place the neck of it around my forehead and ears, so that it hangs down my back, whips gently over my shoulders when I toss my head. A roll of black, thirteen-gallon trash bags rests on the linoleum of the cabinet under the sink, alongside a bottle of Mr. Clean and a heap of dead flies. I rip off a bag, tear holes for my head and arms, let it fall over my bare torso and jeans shorts. Danielle has some fake blood left over from her brother’s vampire costume, and she smears some of it on my lips. I parade up and down the length of the camper between the foldout sofa and the small shower, yammering a mock “Miss America” speech in falsetto. Matt and Danielle are doubled over in the dinette, clutching their sides and wheezing with laughter, tears in their eyes. “You gotta go show my parents,” Danielle insists. “They’ll crack up!”

So I waddle to the door, readjusting the cylindrical couch pillow that constitutes my bosom, and whisper excitedly to them, “I’m getting ready to make my big entrance!” They huddle around me, hands clasped over their mouths to prevent an outburst of laughter that might give away my surprise. I wrap my fingers around the cold inner door handle—then lose it, turning back to my cohorts in laughter. “What should I do?” I solicit them for stage direction. “Just do what you’ve been doing,” says Danielle with a wave of her hand. “It’s great, they’ll love it.” Then she clamps her hand back over her mouth, concealing a grin so big it crinkles the corners of her eyes. I compose myself anew, straighten out my face, and carefully nudge the door ever so slightly ajar.

In a moment I have thrown the door wide, stepped down onto the black metal steps, felt the sandpaper scrape of the tread under my bare feet. I am yowling my Miss America act, flailing my arms in mock elegance. In a moment, the four fire-lit faces of my parents, my father’s cousin and his wife turn from their cigarettes and their stories, their elbows still bent, the brown bottles suspended in the blue night, the first mosquitoes penetrating the cloud of repellent to land, unnoticed, on the backs of their hands; my cousin’s knobby Adam’s apple dips with a staccato swallow while my mother’s loose curls rustle against the back of her tank top as she turns toward me. Four dark mouths fall softly open, rows of nicotine-stained teeth emerging over raw, sunburnt lips. I feel their eyes on me, my own eyes zinging from one to the next, and I launch into my falsetto rendition of “America the Beautiful,” all swooping vowels and exaggerated vibrato. I wait for the laughter, but they just stare.

I wait and wait, and then I fall quiet. My mouth falls open, and I stare back at them. I stumble backward, up the steps, the tread scraping my calves. With a bang, the hollow fiberglass door gives way behind me and I retreat back into the yellow light of our camper, the celebratory arms of a more generous audience. But I push away from my cohorts, withdrawing to the bunk beds in back of the camper where I rip off the trash bag and fall, shaking, into bed. I rub and rub with my fist at the fake blood on my mouth, crashing into the bathroom every few minutes to bore into my reflection, but I can’t tell if it’s going away. I seem to be looking somehow past the red smudge of my lips, past my reflection and through the thin aluminum wall to the gravel and Astroturf, the nylon lawn chairs, seeing only their eyes in the haze of cigarette smoke and mosquito repellent, staring back at me. Their dim, yellow teeth in the firelight.

As of 2016: Andy Harper holds an MFA from the University of Nebraska Omaha and is pursuing a PhD from Southern Illinois University. His recent work has appeared in Lime Hawk, Jenny, Hippocampus, and the museum of americana. He lives in Carbondale, IL, where he studies American literature and teaches college composition.